Collaborative Care requires a team of professionals with complementary skills who work together to care for a population of patients with mental conditions such as depression, anxiety, PTSD, etc. It involves a shift in how medicine is practiced, the creation of entirely new workflows, and frequently the addition of new team members.

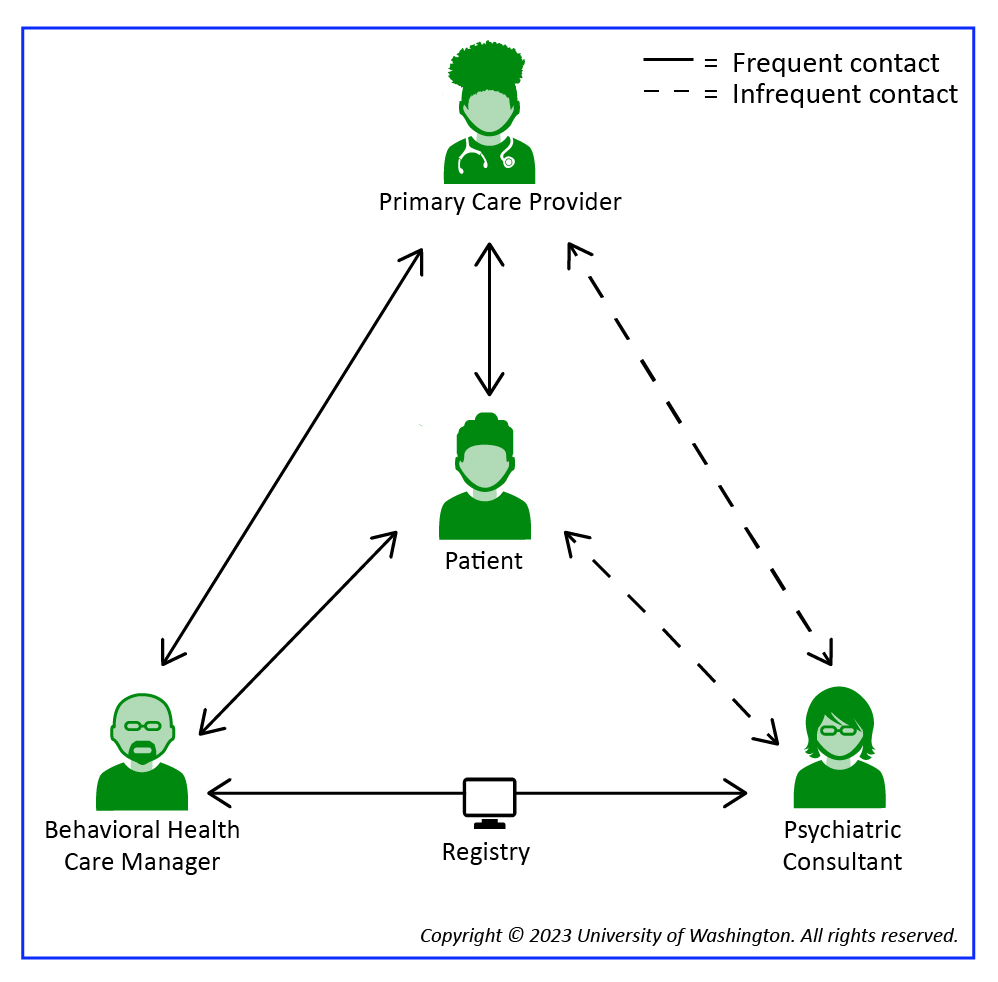

In usual care, the treatment team has two members: the Primary Care Provider (PCP) and the patient. Collaborative care adds two more vital roles: the Behavioral Health Care Manager and the Psychiatric Consultant. Its success relies to a great extent on each member of the treatment team understanding their role and believing they have the knowledge and skills necessary to fulfill that role. Please remember that the principles and core components of Collaborative Care, not just team members, must be in place to practice this model.