An outline of what a Behavioral Health Care Manager should be prepared to discuss about a patient with a Psychiatric Consultant during a consultation.

Audience: Psychiatric Consultant

Psychiatric Consultant Role and Job Description

The Psychiatric Consultant supports the prescribing medical provider and Behavioral Health Care Manager in treating patients with behavioral health problems. They will typically consult with the Behavioral Health Care Manager on a weekly basis to review the treatment plan and provide treatment suggestions for patients who are new or not improving as expected.

The resource below includes a PDF of a comprehensive description of the duties, responsibilities, resource requirements and typical workload of a Psychiatric Consultant.

PHQ-9 Depression Scale Questionnaire

The PHQ-9 is a measurement tool providers can use to ensure measurement-based treatment to target within Collaborative Care. This concise nine-item health questionnaire can function as a screening tool, aids in diagnosis, and measures treatment response.

Advantages of the PHQ-9

- It is shorter than other depression rating scales

- Multiple administration options (in person by a clinician, by telephone, or self-administered by the patient)

- Facilitates diagnosis of major depression

- Assesses symptom severity

- Well-validated and documented in a variety of populations

- Directly based on the nine diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder in the DSM-5

- Valid for use in adolescents as young as 12 years of age

How to Use the PHQ-9

At the initial visit, the PHQ-9 aids in the diagnosis and identification of potential depressive symptoms. At follow-up visits, it measures treatment response. The Questionnaire can be clinician or self-administered.

Scoring the PHQ-9

The PHQ-9 is a tool to assist clinicians in identifying and diagnosing major depression. It has a maximum score of 27. Elevated scores strongly correlate with a major depression diagnosis. However, it’s essential to remember that not everyone with a high PHQ-9 score will have major depression. Trained clinicians must make the final diagnosis.

Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2)

The Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2) effectively screens large groups for depression. It consists of the first two questions on the PHQ-9. If the patient responds affirmatively to either question on the PHQ-2, the PHQ-9 should be administered. No permission is required to reproduce, translate, display, or distribute the PHQ-2.

PHQ-9 Questionnaire and Translations

The PHQ-9, translations of the measure, and an instruction manual are available at www.phqscreeners.com. No permission is required to reproduce, translate, display, or distribute the PHQ-9.

Protocols for Suicide Prevention

The PHQ-9 asks about suicidal ideation, and clinics should have a plan in place for when a patient scores positive on this question. The Protocols for Suicide Prevention in Primary Care assists clinics in refining existing protocol(s) for responding to patients who present with suicidality or violent behavior.

PHQ-9 Aids

Introducing the PHQ-9

To increase staff comfort in discussing the PHQ-9 with patients, the AIMS Center provides the Helping Clinic Staff Talk about the PHQ-9 tool. This resource equips clinic staff to administer the PHQ-9 by addressing commonly asked patient questions.

PHQ-9 Visual Answer Aid

This answer aid visually represents the PHQ-9 answer scale: English | Spanish.

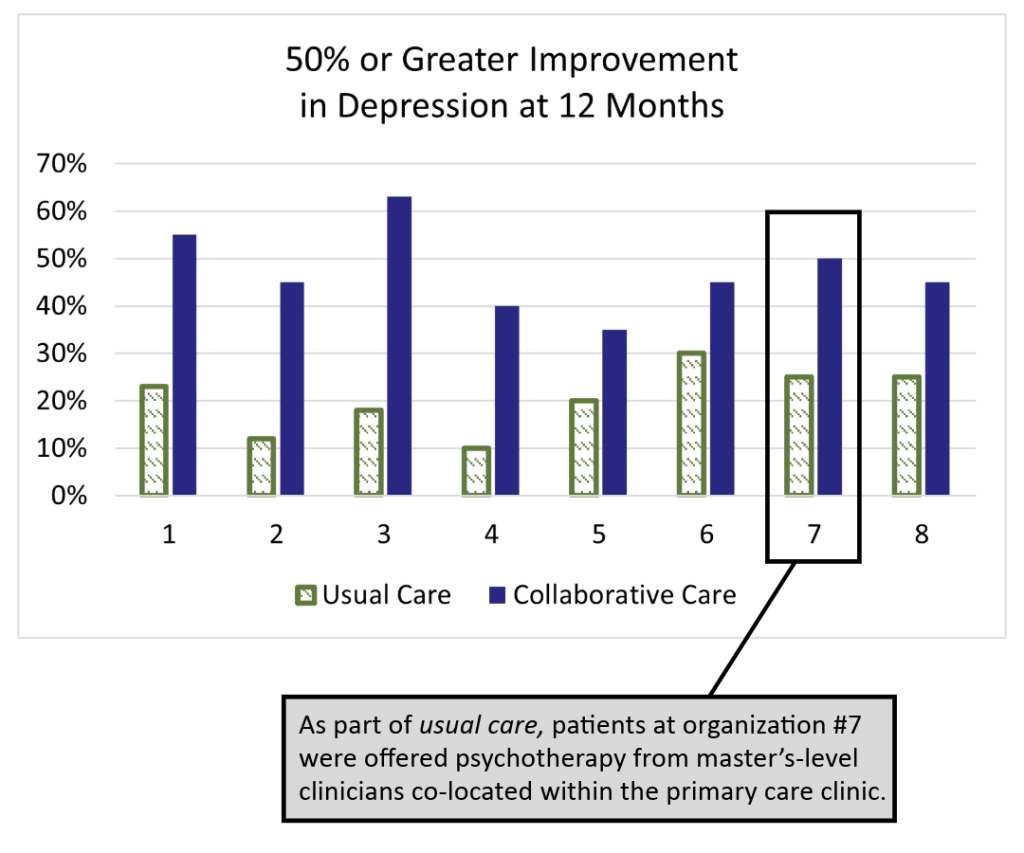

Comparing Collaborative Care to Usual Care

Introduction:

Compared with usual care, Collaborative Care has been shown to improve the effectiveness of depression treatment and lower total healthcare costs. This handout outlines those differences using data from the IMPACT trial.

A printable PDF is available for download; however, please note that this document may not conform to the WCAG-2 accessibility standards.

Comparing Collaborative Care to Usual Care

The IMPACT (Improving Mood: Providing Access to Collaborative Treatment) trial focused on depressed, older adults. Half were randomly assigned to receive the depression treatment usually offered by participating clinics, and half were randomly assigned to receive collaborative care. Collaborative care more than doubled the effectiveness of depression treatment and reduced total healthcare costs at the same time (JAMA, 2002).

Usual Care

50% of study patients used antidepressants at the time of enrollment, but were still significantly depressed.

70% of usual care patients received medication therapy from their PCP and/or a referral to specialty behavioral health.

Only 20% of patients showed significant improvements after one year, which matches national data for depression treatment in primary care.

Collaborative Care

On average, twice as many patients significantly improved. The difference was statistically significant in all eight healthcare settings. Why?

- Patient-Centered Team Care

- Population-Based Care

- Measurement-Based Treatment to Target

- Evidence-Based Care

- Accountable Care

AUDIT-C

The AUDIT-C is a 3-item alcohol screen that can help identify persons who are hazardous drinkers or have active alcohol use disorders (including alcohol dependence). The AUDIT-C is a modified version of the 10-question AUDIT instrument.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder subscale (GAD-7)

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) subscale of the Patient Health Questionnaire (GAD-7) is a quick and easy tool to help identify patients with anxiety and monitor treatment response. The GAD-7 is available free for clinical use in a variety of languages at the link below.

Resource Document on Risk Management and Liability Issues in Integrated Care Models

For psychiatrists considering future roles in integrated care systems, it is important to clarify malpractice liability when providing advice about care for patients for whom the psychiatrist may not be the primary prescriber. This resource document provides background information on medical malpractice cases, defines the doctor-patient relationship, distinguishes the different forms of consultation offered to primary prescribers, describes the duty of the psychiatrist across the spectrum of roles on a patient care team, and, finally, makes recommendations to reduce the risk of malpractice issues.

Example Disclaimer for Psychiatric Consultants

It is important to clarify malpractice liability when providing care advice to patients where the psychiatrist may not be the primary prescriber. An example disclaimer regarding EMR reviews is below. Pairing this information with the name and contact information of the Psychiatric Consultant makes it easy to facilitate communication about recommendations. To the AIMS Center’s knowledge, this type of disclaimer has not been tested in a court case.

“The treatment considerations and suggestions in this case review are based on consultations with the patient’s Behavioral Health Care Manager and a review of information available in the care management tracking system. I have not personally examined the patient. All recommendations should be implemented with consideration of the patient’s relevant prior history and current clinical status. Please feel free to call me with any questions about the care of this patient.”

The Resource Document on Risk Management and Liability Issues in Integrated Care Models provides additional information on liability issues.

Example Psychiatric Consultant Services Contract

An example of a Psychiatric Consultant services agreement between a Community Mental Health Center and a Federally Qualified Health Center for organizations that may be interested in contracting for Psychiatric Consult services.

Please note: Contract language and template example is provided with permission from Valley Cities Behavioral Health Care.

PMQ-9 (Spanish)

The Spanish version of the Patient Mania Questionnaire (PMQ-9) is a nine-item scale used to assess and monitor manic symptoms. The PMQ-9 Mania Questionnaire complements use of the PHQ-9 for depressive symptoms to inform measurement-based care. It is also suited for use in mental health care settings. An English version of the PMQ-9 can be found here.