The AUDIT-C is a 3-item alcohol screen that can help identify persons who are hazardous drinkers or have active alcohol use disorders (including alcohol dependence). The AUDIT-C is a modified version of the 10-question AUDIT instrument.

Audience: Behavioral Health Professional/Care Manager

Comparing Collaborative Care to Usual Care

Introduction:

Compared with usual care, Collaborative Care has been shown to improve the effectiveness of depression treatment and lower total healthcare costs. This handout outlines those differences using data from the IMPACT trial.

A printable PDF is available for download; however, please note that this document may not conform to the WCAG-2 accessibility standards.

Comparing Collaborative Care to Usual Care

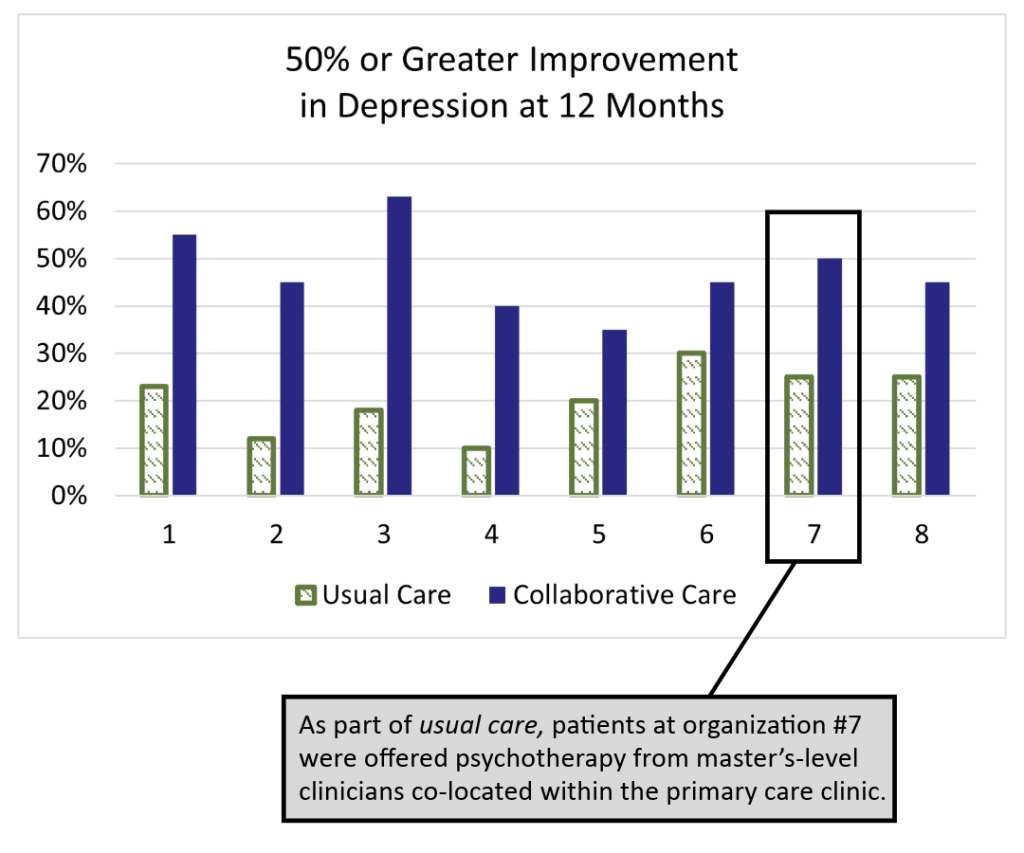

The IMPACT (Improving Mood: Providing Access to Collaborative Treatment) trial focused on depressed, older adults. Half were randomly assigned to receive the depression treatment usually offered by participating clinics, and half were randomly assigned to receive collaborative care. Collaborative care more than doubled the effectiveness of depression treatment and reduced total healthcare costs at the same time (JAMA, 2002).

Usual Care

50% of study patients used antidepressants at the time of enrollment, but were still significantly depressed.

70% of usual care patients received medication therapy from their PCP and/or a referral to specialty behavioral health.

Only 20% of patients showed significant improvements after one year, which matches national data for depression treatment in primary care.

Collaborative Care

On average, twice as many patients significantly improved. The difference was statistically significant in all eight healthcare settings. Why?

- Patient-Centered Team Care

- Population-Based Care

- Measurement-Based Treatment to Target

- Evidence-Based Care

- Accountable Care

PHQ-9 Visual Answer Aid

This answer aid is a visual representation of the PHQ-9 answer scale. Behavioral Health Care Managers can use this resource alongside the PHQ-9 during screening to get a fuller understanding of how their patient is feeling.

Relapse Prevention Plan (Spanish)

Depression can occur multiple times during a person’s lifetime. The purpose of a relapse prevention plan is to help the patient understand their own personal warning signs. These warning signs are specific to each person and can help the patient identify when depression may be starting to return so they can get help sooner – before the symptoms get bad. The other purpose of a relapse prevention plan is to help remind the patient what has worked for him/her to feel better. The relapse prevention plan should be filled out by the Behavioral Health Care Manager and the patient together.

The English version of the Relapse Prevention Plan can be found here.

PHQ-9 Visual Answer Aid (Spanish)

This answer aid is a visual representation of the PHQ-9 answer scale in Spanish. Behavioral Health Care Managers can use this resource alongside the PHQ-9 during screening to get a fuller understanding of how their patient is feeling.

Relapse Prevention Plan (Generic)

The purpose of a relapse prevention plan is to help the patient understand their own personal warning signs. These warning signs are specific to each person and can help the patient identify when their mental health is declining so they can get help sooner – before the symptoms get bad.

The other purpose of a relapse prevention plan is to help remind the patient what has worked for them before to help them feel better. The relapse prevention plan should be filled out by the Behavioral Health Care Manager and the patient together.

Tips for Discussing Trauma During an Initial Assessment

Trauma can increase the risk of health, social, and emotional problems. Despite the high prevalence of patients with a past history of trauma, few clinics or Collaborative Care teams have a protocol for addressing it. These three tips can help clinicians safely and effectively discuss the trauma history of their patients during their initial assessment.

Caseload Size Guidance for Behavioral Health Care Managers

This guidance will help health care organizations think about the questions to ask when determining an optimal caseload size for a Behavioral Health Care Manager. In addition, we provide two examples of different caseloads and considerations for scheduling patients.

Developing Protocols for Suicide Prevention in Primary Care

Introduction

Primary care clinics have a responsibility to provide effective and efficient suicide safe care that is accessible to all patients and staff. Developing a thoughtful and clear protocol and workflow for responding to suicidality in your primary care setting will empower staff to know how to act as well as help keep patients and staff safe.

The resource below contains information about screening and identification, conducting risk assessments, response and follow-up to suicide risk, as well as several additional resources. This information is intended to guide primary care clinics to refine existing protocol(s) for responding to patients presenting with suicidality or violent behavior in a primary care clinic.

A printable PDF is available for download; however, please note that this document may not conform to the WCAG-2 accessibility standards.

Developing Protocols for Suicide Prevention in Primary Care

Primary care clinics have a responsibility to provide effective and efficient suicide safe care that is accessible to all patients and staff. Developing a thoughtful and clear protocol and workflow for responding to suicidality in your primary care setting will empower staff to know how to help keep patients safe. This information is intended to guide primary care clinics to refine existing protocol(s) for responding to patients presenting with suicidality in a primary care clinic.

Principles

All clinic staff are informed and supported

One-page workflows for responding to suicidal ideation should be easily accessible to all staff (not just the behavioral health staff or the clinic manager). These workflows should clearly outline when and how to respond, who to engage, and list internal and external resources. The 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline or other relevant emergency/crisis numbers are easily available. And staff are informed on how to contact the crisis response teams if available in your setting.

Collaboratively develop safety plans

A safety plan provides guidance and resources for the patient to reduce their risk of suicidal behavior. This is a collaborative document that includes holistic assessment paired with individualized intervention, as opposed to a safety contract, which is an agreement not to self-harm. There is no evidence that contracting for safety with a patient is effective at reducing suicides. In addition, contracts have no legal meaning and may give a false sense of security to a provider.

Take risk seriously

Primary care clinics should be screening patients to identify those at risk of suicide. Appropriate risk assessment and intervention should be completed for every patient identified with risk of suicide, every time.

Suicide Prevention Protocol Elements

The below sections provide descriptions of the key suicide prevention protocol elements, as follows:

- Screening and identification of suicide risk

- Asking about and assessing suicide risk level

- Responding to suicide risk level

- Follow up & next steps in care

1. Screening and identification of patients at risk of suicide

Any patient presenting for mental health or substance use treatment should be screened for thoughts of suicide with a validated screening tool. The PHQ9 question #9 is one example. It reads, “Have you been having thoughts that you would be better off dead or thoughts of hurting yourself in some way?”. When a patient scores positive for suicide risk, further information should be gathered.

Resource:

2. Ask about and assess suicide risk level to determine next steps

To determine suicide risk level, a trained staff person should administer a validated screening tool like the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS), Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) and/or the Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage (Safe-T). Providers should be trained to communicate with patients who are suicidal in a calm, curious, and caring manner. Validated tools when combined with clinical judgement can help determine levels of risk and aid in making clinical decisions about care.

In general, suicide risk level can be grouped into two categories:

Non-Acute Risk

Imminent risk of completing suicide is not identified; indicates the patient can safely continue treatment in primary care with appropriate intervention.

Acute Risk

Imminent risk of completing suicide is identified; indicates patient should be under safe observation until a crisis response team completes an evaluation or patient is taken to an Emergency Department for potential hospitalization.

Levels of risk can be classified differently depending on the validated tool used. Some tools, like the C-SSRS or SAFE-T assign “high”, “moderate” or “low” values influenced by modifiable risk factors and protective factors. Classifications like these support interventions that are responsive to patient risk level.

Resources:

- National Institute of Mental Health: ASQ Toolkit

- The Columbia Lighthouse Project: SAFE-T with C-SSRS

3. Responding to suicide risk level

Non-Acute Risk Interventions: If risk is non-acute, the next step is to develop a collaborative safety plan. This is an important clinical component of treating a patient in an outpatient setting. Even when a patient is experiencing passive suicidal ideation, a safety plan should be done because suicide risk is not fixed and can change over time. Safety planning should address risk factors that can be modified, including limiting access to lethal means.

Acute Risk Interventions: If risk is acute, the provider should have a direct conversation about next steps for maintaining the patient’s safety. A clinic staff member should remain with the patient until the patient is evaluated by a crisis response team or in safe transport to an Emergency Department. Clinic staff should be trained on how to coordinate and provide relevant chart notes for the referral. A plan should be in place for appropriate action if a patient refuses care or leaves the clinic against medical advice (AMA). This may include contacting a crisis response team or the police.

Resource(s):

- Stanley-Brown Safety Planning Intervention: Safety Plan Template

- ZERO Suicide: Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (CALM)

4. Follow up & next steps in care

The clinic should have a clear process to follow up with patients who have presented with suicidal risk. This includes clear guidelines on how to regularly track, follow up on and review safety plans with patients. Staff should be trained in where to find completed plans in the EHR.

For patients who receive further evaluation by a crisis response team or Emergency Department, the primary care clinic should have a plan for coordinating care, including who is responsible for documenting and communicating evaluation outcomes and patient care plan with the team.

The clinic should offer support and follow up to staff who may be impacted by a patient treated for suicide risk or who dies by suicide.

Resource(s):

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center: Safe Care Transitions

- ZERO Suicide: Care Transitions

AIMS Caseload Tracker

The AIMS Caseload Tracker is a web-based patient registry thoughtfully designed by the AIMS Center to support behavioral health teams working in Collaborative Care and other integrated care settings. The software can be licensed for use by health care organizations from the University of Washington.

Further details can be found on the AIMS Caseload Tracker webpage.