What is Measurement-Based Care?

Measurement-based care means using clinical tools to track a patient’s progress over time. Using clinical outcome measures at multiple, repeated timepoints along the treatment pathway is still emerging in some areas of the behavioral health world. However, it has been a standard in other areas of healthcare for decades.

For example, when someone visits a primary care clinic, their blood pressure is usually taken. This helps guide treatment decisions. That’s measurement-based care in action.

In behavioral health, many clinics use screening tools for conditions like depression or anxiety. But they often don’t follow up with repeated measurements. Regular follow-ups are essential to determining whether treatment is effective or in need of adjustment.

Commonly Used Measures

Various well-validated measures can help track treatment progress over time. Some example measures include:

| Measure | Target | Adults | Adolescents | Pediatric |

| PHQ-9 | Depression | ✔️ | ✔️ | |

| PMQ-9 | Mania | ✔️ | ||

| GAD-7 | Anxiety and related disorders | ✔️ | ✔️ | |

| PCL-5 | PTSD | ✔️ | ✔️ | |

| SCARED | Anxiety | ✔️ | ✔️ | |

| SMFQ | Depression | ✔️ | ✔️ | |

| Vanderbilt | ADHD | ✔️ |

Why Measures Matter

Measures are important in identifying individuals who may otherwise be missed as needing behavioral health support. However, their most important role is measuring the effect of treatment on symptoms. Once a patient is identified as having a behavioral health condition and has started treatment, it’s critical to re-measure the symptoms at each contact so that the treating provider has specific information on whether symptoms are improving and, if not, which symptoms are not.

There is some concern that measuring mental health with a validated rating instrument invalidates the patient’s feelings or experience, or else disregards the complexity of the patient’s story. While these measures offer important information about the patient, they are not meant to represent the entire clinical picture of the patient, nor to replace the provider’s clinical judgment. They are a key tool to assist the clinician and patient with identifying the specific symptoms that cause difficulty for the patient and how those symptoms respond to treatment over time.

Using Data to Adjust Treatment

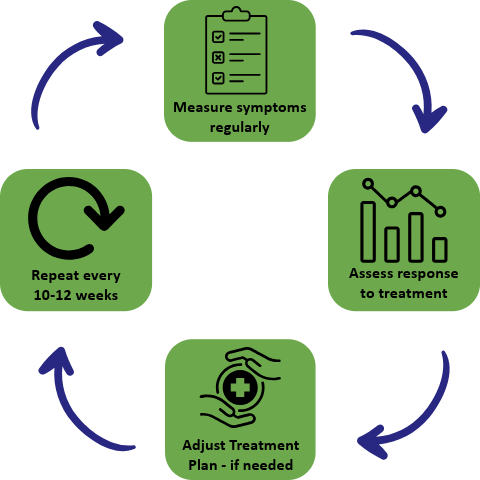

In Collaborative Care, treatment should change if symptoms don’t improve. Providers should aim for at least a 50% reduction in symptoms. If that doesn’t happen, the plan should be adjusted.

Frequent measurement of symptoms informs the care team whether the patient has had a full response, a partial response, or no response to treatment. If there is a partial response, these measures also provide clues about which symptoms are improving and which are not. This information is critical when making decisions about treatment adjustments.

Collaborative Care requires a change in the treatment plan every 10-12 weeks if the patient’s symptoms haven’t improved by at least 50%, as assessed by a validated measure. This might mean adjusting medication, adding therapy, both, or vice versa. This approach helps avoid the stagnation that can occur in traditional care settings and is likely one of the key factors behind the better treatment outcomes that Collaborative Care can achieve.